WOP! A Documentary History of Anti-Italian Discrimination in the United States, Edited by Salvatore J. LaGumina

I found this thing called WOP! in a now-gone used bookstore in exurban Connecticut a few years back. When I took it up to the counter, the owner said, “I’m so glad someone’s finally buying this.” Perhaps because he wanted the book out of his store? It was published in 1973 by Straight Arrow Press, one in a series called “Ethnic Prejudice in America”; the other books had similarly provoking titles such as MICK! and KIKE!

I do wonder how much thought the publisher gave to the idea that a reader might not want to go around with a book called WOP!, particularly one with a photo like this one on its cover. It’s credited to Robert Altman (and maybe someone can hip me to what film it’s from) and shows a super G in black fedora, black chalk-stripe suit, black shirt, and wide white tie, shoving a sloppy forkful of spaghetti into his mouth. A spotty yellow napkin sits like an awkward bird on his shoulder and a “violin” case rests on his knee. It is so wrong on so many levels that it is uniquely fascinating—it’s a ’70s version, complete with sideburns, of a ’30s mafioso and seems to belong to the continuum of Italian farces, a sort of debased version of representations from films like Alberto Lattuada’s Mafioso or a Pietro Germi satire, rather than to any of their Italian-American cousins. I mean, at least get your stereotypes right! Inside the book I was relieved to read this statement by Professor LaGumina: “The photograph appearing on the cover was chosen exclusively by the Publisher contrary to the view of the editor.” Straight Arrow Press was also the wellspring from which sprang Rolling Stone magazine.

The photo not only misrepresents the book but points it in a different direction—it seems more appropriate for a discussion of what constitutes satire, and when does satire cross a line into defamation and toxicity (and become fodder for the amusement of bigots—I think of this story of why Dave Chappelle decided to pull the plug on “Chappelle’s Show”). The book, instead, is not so much a discussion of Italian-American representations as it is a compendium of writings, and some cartoons, of the worst of them. The most blinkered, prejudiced, hate-filled.

WOP! is nearly fifty years old and includes articles written as early as the 1830s. As such, it’s a time capsule. While it may have been the case in 1973 that, as Professor LaGumina writes, “Contemporary Italian-Americans generally maintain they are still being victimized by prejudice and discrimination,” it’s 2020 now. For the most part, Italian-Americans have been stirred so fully into that questionable thing, the Great American Melting Pot, that any current claims of discrimination frankly seem ridiculous to me. What refuses to die, however, are the idiotic one-note representations still somehow ascendant: the Italian-American as an endearing dummy hawking some kind of theoretically “Italian” foodstuff, the Italian-American as a no-class loudmouth or, most indelibly, the Italian-American as a mobster.

The mother—?—of the comic Italian immigrant ad, the 1969 Alka-Seltzer “Mamma mia, that’s-a spicy meat-ball-a” commercial. Since then, there have been innumerable mooks hawking various sandwiches, the 1998 Pepsi commercial with the cute little girl who talks like a mafioso (weirdly enough, played by Jessie Eisenberg’s little sister Hallie), and many more examples too wearying and repetitive to go into. Maybe most recent is a 2018 print ad that Eataly in Chicago used to sell truffles: “BRING HOME AN ITALIAN … WORTH THE SMELL.”

The relentless appetite for depictions of Italian-American criminality will be with us for a long time, sure as Scorsese’s The Irishman was the pick hit film of 2019—though am I having it both ways when I say I love that film? I found it subtle, thoroughly meta, and evocative of a vanishing way of being in the world, as well as what is maybe a peculiarly Italian-American type of heartache. The “crime story” was a framework for a deeper narrative, one about aging and betrayal.

“È buono, no?” Joe Pesci as Russell Bufalino and Robert De Niro as Frank Sheeran in The Irishman. Old jailbirds now, they once again break bread together. Pesci has never been better.

WOP! is divided into seven chapters, starting with “Anti-Italianism—The Embryonic Stage (Pre–1880)” and rolling forward through subsequent eras, with the bulk of the book concentrated on 1890–1914, the “High Tide of Italian Immigration.” Anti-Italian discrimination appears to have lessened significantly after the U.S. entered World War II, perhaps because of strong Italian-American support for the war effort—“Virtually the entire Italian-American community dropped whatever lingering support there was for Mussolini”—and the huge number of Italian-American soldiers serving in the war (my father Cipriano and my indefatigable 98-year-old Uncle Ray two among “several hundred thousand” who served in the war or in its immediate aftermath). The book winds up with “The Post–World War II Period—Ongoing Problems,” which has the curious effect of sounding like some annoyed grandma saying, What can you do?

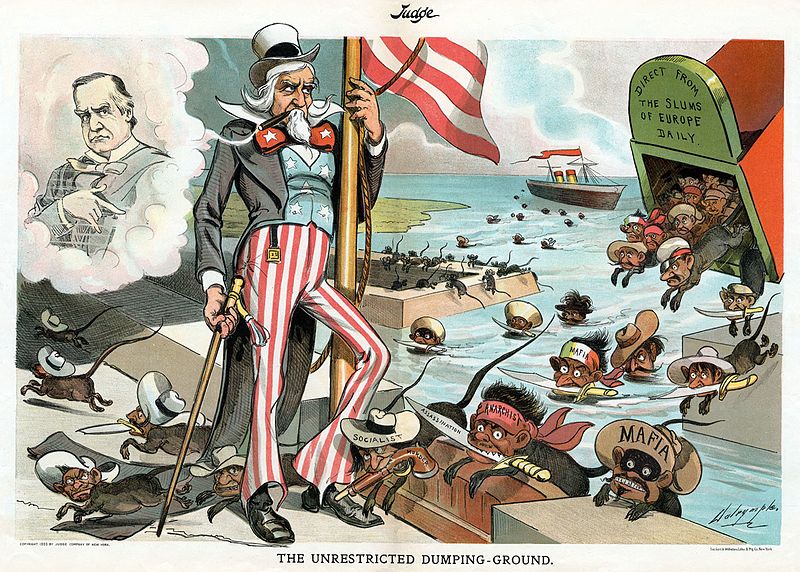

Professor LaGumina seems to have been tireless in his compiling of material. Many of the primary sources he drew from are newspapers and journals that have long ceased operation—everything from satirical journals like Judge that reveled in offensive stereotypes, to what appear to be more neutral publications like the New York Herald, Century Magazine, and the Illustrated American. One particular font of xenophobia and reliably disgusting hate writing is the New York Times, back in the pre-Ochs era when it appears to have been a WASP stronghold. Other more benign sources include various national commission reports, court documents, the Congressional Record and, on the side of the angels, a letter from Vito Marcantonio.

“I am a radical and I am willing to fight it out . . . until hell freezes over.” The great Vito Marcantonio with children in his East Harlem district. From a terrific article about Marcantonio, “New York’s Last Socialist Congressperson,” by Benjamin Serby at Jacobin: “Over twenty thousand supporters turned out for Marc’s funeral, where the great civil rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois eulogized him as ‘a politician in the finest sense of the mutilated word,’ adding: ‘in this era of national cowardice, there were not many of his courage.’”

In the first chapter, which covers the era just before mass emigration from Italy, the stereotypes immediately start to take shape. Initially, much of the prejudice seems cloaked in phony concern: These unscrupulous padroni duping the poor pick-and-shovel men! These ignorant peasants, benighted by the priests! These ragamuffin children sent over to beg—it’s a form of white slavery! All of this is of course masking the central belief that these people shouldn’t be here at all.

As the chapters roll on, the popular stereotypes quickly gel and come in exhaustive, repetitive detail: Italian immigrants are dirty; lazy; clannish; ignorant; of “low moral character”; “naturally dishonest.” They are short and swarthy. Most carry knives and stink of garlic. They are criminals or non-contributing members of society holding out their hands for an easy payday. If the latter, they are touching, childlike. The Southern Italians are the worst, they are not only really short and swarthy, but they’re mostly illiterate.

Louis Dalrymple’s The Unrestricted Dumping-Ground, published in Judge, 1903. Change a few labels and this would be absolutely at home in Trump’s U.S.A.

Is it too obvious to say that something disturbing about much of this writing is how utterly the journalists delight in the descriptions of squalor, suffering, and infamy? There’s a hot little exposé, “The Italian Slave-Trade,” by “a reporter” in the New York Times of July 7, 1872, sort of Dickensian in its specificity and pathos, if not in its impossible-to-hide revulsion. The reporter writes about the traffic in Southern Italian children—sold by their impoverished parents, shipped to the U.S., furnished with musical instruments by blood-sucking padroni, and sent out to beg on the streets of New York:

There are few readers of the Times who have not seen these unhappy ones, their poor faces blue and wrinkled, with the terrible smarting of the frost, bobbling about in shoes a world too wide for their lithe small feet, broken, and letting in the melting snow and slush at every tread, their hands muffled in their scanty jackets, with tears of torture trickling down their brown, innocent faces.

With the help of an interpreter, the reporter makes an expedition into the slums of Crosby Street to uncover more. It is a bit like a trip to the underworld:

Hideously homely women, dressed with outlandish bodices and with naked feet thrust into their slippers, kept hastening into the grocers and returning with loaves of Italian bread and tag-ends of American cheese, old, strong and hard as brick-bats. Some of these women were quite old, and realized the idea of witches perfectly. There was one in particular who had two enormous warts upon her chin, from which straggled some bunches of coarse white hair ….

The reporter and his interpreter follow the old woman, and she turns to them, “evidently believing, from the comparative splendor of our appearance, that we were going to give an evening party and wanted a harp and violin.” She directs them to the room of three brothers who really can play their instruments, as opposed to the other little beggar children, and the reporter meets “a very slim, gentle young fellow, of nineteen, fair-haired, and blue-eyed, very different from the conventional idea of an Italian.” He handles his violin tenderly, and has “an innate refinement that would have shamed the millionaires of our Northern races.” The reporter is astonished to find such a specimen in such wretched surroundings.

The story goes on, in great detail, about the young Italian’s despair over the trade in children, the hopelessness, the brutality, with a side trip to a nearby apartment where one of the perhaps marginally less evil padroni shows the reporter the sad stuff of his life and his meals, including the “lump of fragrance” that he uses for cheese and his “maccaroni,” which the reporter concludes must be “something like the German noodles.” The trip to the inferno of Crosby Street ends back in the apartment of the angelic violinist, who tells the reporter about a young boy who was horribly abused at the hands of his padrone—tied hand and foot, with pieces of burning rope inserted between his toes—until he escaped to a village somewhere south of New York where an old farmer took him in as a son. For others, however, it was too late. One little boy “who loved music” and who would come to the violinist’s room to warm himself has a terrible end:

He died in this young Italian’s arms, wasted away almost to a shadow, with his fiddle hugged to his worn chest, but when his only friend asked him to pray, “God bless mother,” he raised his head fiercely, whispered, “She sold me,” and fell back dead.

And thus does our reporter close the book on all things Italian, leaving the one lone angel to rot in the irredeemable hellhole of Crosby Street.

There are numerous articles like this—full of vivid, lavish, lurid detail. Even more prurient (and creepily enthralling to read, at least from the safe distance of a hundred-plus years) is another New York Times piece, from 1879, where the reporter watches the steerage passengers arrive in New York. The 200 Italians are “the filthiest and most miserable lot of human beings ever landed at Castle Garden.” Among these superlatives is one passenger of particular fascination, a “frightfully-misshapen object who hobbled along on all fours like a dog”:

The fingers of both hands were twisted in a shocking manner and were covered with large lumps. Both legs were twisted out of shape, and were abnormally short, one being longer than the other, and one was entirely paralyzed. Two flat blocks of wood were attached to his arms by straps, and in this way he managed to drag himself along. A rather comely Italian woman of 36, and two children—a boy of 3 years old and a girl of 18 months—were with him. Being questioned privately, he gave his name as Vito Museo …. In response to an inquiry to why [the wife] had married Museo, she answered that he was abused by the neighbors on account of his deformity and she took pity on him—she wished “to keep his linen clean.” She said that when he was 7 years of age a man who had quarreled with his father threw him into the fire out of revenge.

As I read on through descriptions like these, through the stories of mentally deficient organ-grinders, picturesquely dressed lazzaroni, knife-wielding outlaws, crime-condoning primitives, and even of something called the “Italian flea”—an insect “much smaller than the flea born and bred under our generous institutions and … very nearly twice as malignant,” something struck me. In the March 23, 1901 article “Startling Facts About Our Pauper Italian Immigrants” written by one Regina Armstrong for Leslie’s Illustrated, among conclusions such as “A little macaroni for the day, a thrumming guitar or mandolin or sither for the merry passing of the night hours, playing under windows and eliciting a few centimes, and [the Italian] is content,” I found it put into words:

Their knack of prettifying everything is remarkable; never the teamster so poor who has not bells and ornaments built up on his saddle, and perhaps roses on the bridle of his horse. If he have fruit or vegetable to sell, his basket or cart has a branch of green and flowers set up in a really beautiful decorative sense, and the most miserable little store is made attractive by the way the ware is exposed. A box of a stall where vegetables are sold will have its melons laced around by colored strings or wisps of green, and so tied upon the wall outside, a picture to delight the eye—dirty, perhaps, nearly always so—but even in dirt there is color.

“Even in dirt there is color.” Are these noisy, stinky, roiling Italian immigrants a kind of outlet for these journalists? Their conduit to something more expressive, more raging, more alive? Are these Italians in some sense their muses? A whiter, more accessible version of what would come to be called “the Magical Negro”? In an article called “The Italian Problem” from July 3, 1909, in Harper’s Weekly—a piece that is, if paternalistic, more sympathetic than most—the writer defines the Italian character, much of it in terms of the Italian’s presumed usefulness in his adopted country:

We like the Italian as a laborer, like him fairly well even as a citizen; but as a sojourner he has points that are not satisfactory. He comes, for the most part, from southern Italy, and his training there seems to have qualified him very imperfectly to appreciate our institutions. He believes to excess in self-defence and in personal reprisals, and is distrustful of law and legal methods. When he is good he is very liable to be victimized by the bad men of his race, and when he is bad he is bad in an underhand, violent, grand-opera way that is a scandal to our citizens.

This bad man is a “scandal” but also perhaps a magnet, a form of entertainment. Coming in a direct line from this is the figure of the mafioso—superlative, insatiable, larger than life. A caricature is something you can draw in a few broad strokes. Draw it large enough and you can see it from far away, with no need for closer scrutiny.

As the timeline of the book progresses—and perhaps, as the novelty of the Italian immigrants’ “colorful” ways begins to wear off—resentment of Italians coalesces around two things: their “temporary” status, given that so many were seasonal workers who would return to Italy with their wages, and what is characterized as their refusal to assimilate, instead confining themselves to America’s many Little Italies. Nonetheless, the charges of ignorance, lawlessness, and stupidity keep on coming, to wearying effect. Besides being inaccurate, offensive, and toxic, here’s the thing about prejudice: it’s boring. It starts and ends with itself. It revels in unknowing. It kills thought in the cradle. It is like Donald Trump contemplating his next border wall or cheeseburger while Black men are getting murdered by cops in the street.

Listen to Mussolini on British Movietone News in 1929 saying, among other things, “Make America great” (comes in at about 1:10). This came to my attention as part of a fascinating talk that Giorgio Bertellini gave around his book, The Divo and the Duce: Promoting Film Stardom and Political Leadership in 1920s America, at the Calandra Institute in late 2019.

Hovering around all of this is of course the issue of race, as defined in terms of Black or white. During the time of much of these writings, Italian-Americans had not quite become white yet. They were still in an uncomfortable-making neither/nor state, a state that seems to have been magnified or diminished based on factors such as what part of Italy these Italians came from—the further south, the more questionable their perceived whiteness—and what part of the U.S. they were living in, though generalizations are tough to make. One incident given a lot of space in WOP! is the infamous lynching of eleven Italians in New Orleans in 1891. Much has been written about this lynching, and in 2019, LaToya Cantrell, the first Black female mayor of New Orleans, apologized for it.

What does it say that it takes an African-American woman, a member of a group that is among the least culpable and most oppressed, to make such an apology?

Accused of assassinating police chief David Hennessy—with much of the evidence of their guilt resting on the dying Hennessy’s words that he had been attacked by “the dagoes”—the eleven Italians were attacked in jail and killed by a mob. This mob, as LaGumina writes, was “led by men of good standing in the community.” He goes on to write, “Article after article in the newspapers of the day readily assumed that the Italians were properly punished.”

Characterizations are particularly charged in these excerpts, such as these words from the New Orleans Times-Democrat: “The little jail was crowded with Sicilians, whose low, repulsive countenances, and slavery attire proclaimed their brutal natures”—note those words, slavery and brutal, aligning these Sicilians with Black people and signaling justification. Over-the-top speechifying rules the day, as in this article from Leslie’s Weekly: “Probably no reasonable, intelligent, and honest person in the United States regrets the death of the eleven Sicilian prisoners in the New Orleans jail …” Upstanding Yankee senator and thoroughgoing racist Henry Cabot Lodge goes through some violent rhetorical contortions to conclude that this was not “mere riot” but “wild justice,” and that the only way to end the cycle of violence is to restrict immigration: “Societies or organizations which regard assassinations as legitimate have been the product of repressive government on the continent of Europe …. If we permit the classes which furnish material for these societies to come freely to this country, we shall have these outrages to deal with …” Mutatis mutandis and here we are in Trump’s U.S.A.

Dalrymple strikes again. From the entry, “March 14, 1891 New Orleans lynchings,” on Wikipedia.

How generally known is it that Columbus Day was first celebrated in 1892, a year after this lynching, and that it was a direct result of it? As Brent Staples recently wrote in his superb, comprehensive article “How Italians Became White,” “Few who march in Columbus Day parades … are aware of how the holiday came about or that President Benjamin Harrison proclaimed it as a one-time national celebration in 1892—in the wake of a bloody New Orleans lynching that took the lives of 11 Italian immigrants. The proclamation was part of a broader attempt to quiet outrage among Italian-Americans, and a diplomatic blowup over the murders that brought Italy and the United States to the brink of war.” Columbus Day was not officially made a holiday until much later, thanks to various lobbying efforts by Italian-Americans—or a certain conservative strain of Italian-American, it should be said. I am all for burying this holiday in favor of Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

Maledetto Cristoforo Colombo e quando ha scoperto l’America! What a crying shame that slaver and genocidal murderer Columbus, who did not “discover” America so much as claim it and exploit it, had to be the guy chosen to represent Italian-Americans. For an informed, nuanced discussion of Columbus Day, read “Recontextualing the Ocean Blue,” by Laura E. Ruberto and Joseph Sciorra.

… speaking of monuments meeting their just deserts, it was a joy to see the statue of racist thug and two-term Philadelphia mayor Frank Rizzo finally come down. Rizzo did something to offend everyone, and easily tossed off words like these, said during his 1975 reelection campaign: “Just wait after November, you’ll have a front row seat because I’m going to make Attila the Hun look like a faggot.”

Sometimes I think it would be great to pick a bona-fide Italian-American hero to name a day for, but more often I think that the moment for this has passed. The spirit does live on in local celebrations of saints’ feast days, such as the Feast of St. Anthony that I grew up with while generally going out of my mind with alienation, disaffection, and ennui in Wilmington, Delaware.

Inside this seemingly happy child beat a heart of despair.

WOP! also touches on discussions of la Mano Nera (the Black Hand), the extortion racket that was very much present in the U.S. at least through the 1930s. My mother Colette used to tell a story about being newly arrived in Philadelphia as a little girl, and seeing a new friend draw back in terror at the sight of black handprint left on the family’s apartment door. The Black Hand seems to have been more a method of extortion than an organization per se; its very unknowability no doubt kept people cowering and in line. Included in WOP! is a brief discussion of Joseph Petrosino, storied lieutenant of the NYPD, who started the “Italian Squad” and busted up much of the Black Hand’s power before being targeted and killed in Palermo while chasing down the criminal element in 1909.

Movie poster for Pay or Die, the 1960 biopic about Joseph Petrosino who is played by Ernest Borgnine “with modesty and courage,” as LaGumina writes. The endlessly smiling Zohra Lampert, whose parents were Russian, plays his wife Adelina, presaging her 1961 role as another sympathetic Italian wife, Warren Beatty’s consolation prize in Splendor in the Grass (and the “Italian” she speaks in that film is quite astonishing). Not sure who is in the mood for a good-cop movie right now, but Pay or Die streams on YouTube, the version I found with Spanish subtitles:

Other sections in WOP! that struck me include a brief passage called “An Italian-American Legislator Defends Himself,” transcribed from the Congressional Record—as Senate.gov defines it, the “substantially verbatim account of the remarks made by senators and representatives while they are on the floor of the Senate and the House of Representatives.” It shows New York’s own Fiorello LaGuardia to beautiful, feisty effect. When one Representative Summers of Washington refers to Italy as being LaGuardia’s country, LaGuardia replies:

My country? My country is the United States. [Applause.] I can understand the desire of the gentleman at a loss to trace a straight line of racial ancestry to boast of a “Nordic” civilization. But do not forget that the people from whence my ancestors came were in England for 200 years, commencing at a period before Christ, civilizing that country. [Applause.]

This is cool and the reader does say, Oh, snap! in her head as she reads it. It becomes something more as the reader continues, and sees the name of another gentleman, this one from Washington, Mr. Johnson. And then maybe the reader will realize this is Representative Albert Johnson, the chief author of the Johnson-Reed Act.

This racist, restrictive act, signed into law in 1924, slashed immigration and established a quota system designed to keep out Eastern and Southern Europeans. It was the very thing that kept my grandfather from coming to the U.S. on his first try in the late 1920s, and the reason why my mother was born in Brazil. The Johnson-Reed Act completely excluded immigrants from Asia, and barred Jews trying to escape Nazi Europe in the 1930s. The Johnson-Reed Act stayed on the books until 1952 and was finally replaced by the Immigration and Nationality Act in 1965.

Che cazzo? you racist schmuck, Ken Cuccinelli. Go here for a cogent article by Maria Laurino, called “Betraying their heritage: Trump’s immigration functionaries fail to understand the lessons of the Italian-American story,” where Laurino writes about Cuccinelli, Mike Pompeo, and acting director of ICE, Matthew Albence, all of them grandchildren or great-grandchildren of Italian immigrants. Laurino makes a point that I hadn’t understood before: “Today’s anti-immigrant rhetoric asserts that the early immigrants came here ‘legally.’ But with the exception of the Chinese Exclusion Act, there were no immigration laws then. The cross-Atlantic journey was harrowing, but if you arrived on America’s shores and weren’t sick, you were let in. Not exactly warmly embraced, but given the chance to establish a life in the United States.” Laurino is the author of a book that means a lot to me, Were You Always an Italian?

WOP! rolls forward with a discussion of Sacco and Vanzetti; touches on the KKK’s anti-Roman Catholicism and attendant anti-Italianism (“The policy of the Klan is to stop the stream of undesirables and thus prevent the gutting of the American labor market”); and includes short excepts from writers and thinkers such as John Fante and Max Ascoli. There is less evidence of Italian-American bashing during WWII, perhaps for the reasons discussed above, or perhaps because new immigrants to hate and ways to hate them had emerged.

“In Little Italy, Italians celebrate the ouster of Fascist dictator Mussolini from the fire escape of 179 Mulberry Street,” July 1943. From the Daily News.

The last chapter of WOP! centers on the ubiquitous one-note stereotype of the Italian-American as mobster. In the nearly fifty years since the book was published, this image has only proliferated—this image and that of its cousin, the gold-chain-wearing, loudmouth spaccone. Exactly why this is the case is a discussion for another day. Otherwise, Italian-Americans mostly have been stirred into the mix, become part of privileged white America. Again, while the stereotypes persist, a person would be hard pressed to see any institutional racism directed at Italian-Americans today. Even using the word “racism” sounds frivolous to me in this context.

Because let’s face it. I will not be treated with suspicion for shopping while Italian-American. I will not be pulled over for driving while Italian-American. I will not be threatened with state-sanctioned violence for birding while Italian-American. I will not be held down and killed by a cop in the street for being Italian-American. What’s the value of even talking about a book like WOP! then? Because we were once those people. We were the hated. We were the targets. How can any of us forget this?

How can any of us not see what we have, the whiteness too many of us think is our birthright, the constructed whiteness that guarantees our inclusion? Especially when this inclusion is systematically denied Black and brown people in this country. Italian-Americans were once pretty brown. Shouldn’t this be a lesson in empathy?

Thanks for this. I’m Italian American, of Abruzzese origin, running an Abruzzese trattoria in South Philly. The argument made at the end of this piece is the one I’ve used to underpin our support (through events and fundraisers at our restaurant) for immigration reform, asylum seekers and refugees, and the rights of undocumented workers. In 2017 I wrote a short piece for Philly Mag touching on the historical commonalities between Italians and today’s disparaged and vilified newcomers and they ways the law has been used to weaponized prejudice and attack specific ethnic groups (my wife’s family is from Shanghai and a village near Guangzhou… her father’s family had somehow made it in before the lapse of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act). This support attracted the attn of Billy Ciancaglini, the doomed GOP candidate for mayor in the last election. He was weaponizing xenophobia in an effort to fire up his base. He attacked us on social media and we dealt with dozens of threats, fake reviews and reservations, and one memorable visit from a bunch of thugs. Our greatest detractors were Italian. As were our greatest defenders. It was a depressing but vivid window on how well or how little some of us remember our history.

My grandfather, born in 1892 and who emigrated in 1909, lived in my Reading, PA rowhome when I was a boy. He told me about the KKK (using a picture in an American Heritage illustrated history of their 1926 march down DC’s Pennsylvania Avenue) and other nativist stupidity. He’d been compelled to change his name from Alfonso Cretarola to Francis Cratil (my name) in an attempt to escape violence and prejudice in PA’s coal regions. He was identified as “dark” on all his documents and as “negro” on his draft card from ’43.

I was a history major as an undergrad and have studied southern Italy, the Risorgimento, Brigantaggio, and the diaspora. (You probably know that ) Many of the prejudices that predominantly southern Italian immigrants faced were based on the studies of Cesare Lombroso, a doctor who’d served in the Army of Piemonte, and had developed theories about the superiority or inferiority of a certain races (through the study of their physical characteristics, especially their skulls and faces). He was convinced he’d found an inferior race, one with a tendency toward criminality, in southern Italy. His museum, which contains the severed heads of southern “criminals” and “briganti” is still open in Torino.

I do think it’s important that we know this history. I would hope that knowing it would compel us to prevent similar injustices from happening to other groups. And I believe the current debate offers us an opportunity to link arms with the Black Lives Matter community.

Anyway, tante grazie.

LikeLike

Francis, thank you most sincerely for your message. I loved reading it. So much insight—I’m grateful you took the time to write me.

How shameful that some awful guy running for mayor would put you in the line of fire like that. Good for you for standing strong. I love the name of your trattoria—I would imagine you chose it for a reason, to reflect your values. Did you grow up in Philly? My grandmother Maria Rachele Auriti was born (di Sipio) on Christian Street in 1906; she went back to Italy as a baby, to her family’s village, Pretoro, in provincia Chieti. My grandfather Marino Auriti was born just a year before yours, 1891, in Guardiagrele, also in Chieti. Where in Abruzzo are your people from? My grandparents eventually settled in Kennett Square, PA. A lot of Abruzzesi in that extended area!

Did you have a lot of time with your grandfather? Mine died in 1980 when I was 12. He was a fascinating, unusual guy, very interior, dour on the outside, dreaming on the inside. He had a fourth-grade education and built a scale model of a fantastic museum called the Encyclopedic Palace in his autobody garage in Kennett; he was posthumously recognized as a self-taught architect and his work went to the Venice Biennale in 2013 (it will always feel unreal to write that sentence). I wrote about him endlessly in the earlier version of my blog.

I actually hadn’t known of Cesare Lombroso and will study on that. My eyes got big when you wrote that severed heads are still on display in Torino … WTF?? There’s still such a divide between the north and the south in Italy, and such an abomination seems a symptom of that, to put it mildly.

About BLM solidarity, I absolutely agree with you. I’ve been going to the BLM protests up here in NYC, and they’ve been tremendous—the leadership is so committed and passionate (and young! one poised young woman leading a march in June was all of 17) and the general feeling is of hope, strength, and a willingness to stand up for justice.

Tante grazie to you!

LikeLike