How unfair to pick on this flimsy little “heartwarming” movie, particularly when the world is hurtling toward ruin. The plot is low-stakes, TV-ready, and based on a true story: a middle-aged Italian American Brooklynite, bereft after losing his mother, opens a restaurant on Staten Island, brings in a bunch of older ladies to cook, endures many trials, nearly loses everything, and ultimately triumphs.

I wouldn’t have gone near it except for having more than one non-New York cousin shyly ask me if I’d been there, to the Nonnas restaurant? One cousin in particular had such a look of sweet longing in his eyes as to make any urge for sarcasm die on my lips. I asked my friend Sîan, a woman deeply immersed in all cultural things Italian American, about the movie and she said, “Oh yeah, it’s totally cheesy, but of course it made me cry.” And went on to say that when the grandmother says perfecto rather than perfetto, she about lost her mind. Sîan earns her bread as an editor.

So I watched the movie. That scene, toward the beginning, where the nonna is in her Brooklyn kitchen making sauce (inevitably “gravy”), nearly made me lose my mind. If one were to track the movie timeline, it’s the nineteen-eighties, though everything is filtered through a hazy lens of nostalgia and looks a lot like the fifties. The little boy who will grow up to be the restaurateur is watching his nonna put the basil in the sauce. He asks her how she knows how much to use, and she says,

You feel it in your heart.

My Italian grandmothers? Hearing this? Would have been like, Too bad that lady is brain damaged. Has anyone in the history of the world ever really said something like this? Of course my grandmothers didn’t have easy lives. They emigrated, lost their homeland, never seemed to take to this country. They were to me haunted, guarded, no-nonsense, my Abruzzese grandmom Maria Rachele melancholy, my Marchigiana grandmom Elsie suspicious, tough as nails. Elsie carried on under terrible circumstances. Her first husband, my grandfather, was gassed in the Meuse-Argonne when he served in World War I and died in 1926, leaving her with three boys under the age of five. She remarried and had three more kids, one severely disabled. She raised all six as a single mother and kept that family together.

Elsie worked and worked, and there was no time for flights of fancy, twinkly basil-sprinkling moments. Though she was, naturalmente, a superb cook. And she no doubt would have told any moping son of hers to get off his culo and get to work.

Who is this Joe, the hero of Nonnas? In another continuum, he’s a mammone, a man-boy, tied to the apron strings, a grown man who likes cars and home cooking and never seems to date. As played by spooky dead-eyed libertarian Vince Vaughn, he does seem genuinely bereft after his mother’s death. Rallying around Joe are his best friend Bruno and Stella, Bruno’s wife (played by Drea de Matteo, who definitely seems like someone who would corner you in the bathroom of your all-girls’ Catholic high school to give you a beat-down after dancing with her boyfriend at the all-boys’ Catholic high school dance). Stella and Bruno get to do all that Italian American Central Casting business, always so fresh, new, and exciting, like last year’s cheesecake.

The decks are stacked for us to root for Joe. And of course we know he’ll succeed or we wouldn’t be watching this. To learn how he’ll succeed we just have to sit through this flaccid movie, which makes minutes seem like hours. There’s lots of boring fetishizing of objects, glossy food porn, unwatchable “comedic” bits like Lorraine Bracco’s character throwing pastasciutta at some hapless senior-center cook, a silly subplot about a girlfriend left behind at the prom, and tangles involving building inspection, cash flow, neighborhood territorialism, etc. My husband, who once watched a significant portion of an eight-hour documentary about nomadic Mongolian sheep herders, kept checking the progress of the movie on the little bar at the bottom of the screen and asking, “How long is this thing?”

However, it’s really rare – and so welcome – to see so many older women together in one movie. Susan Sarandon brings a level of gravity that’s almost startling, Bracco gets to be unsexy, and Brenda Vaccaro, at eighty-five, shows herself to be a real trouper (and seem to be breathing a lot easier than she did in those old Playtex tampon commercials. They really used to freak me out. Was she a smoker? Who did the sound edit? So many questions). And I must say that Talia Shire is terribly adorable as the tiny, peaceable nun. And the nun is a lesbian! My brief fit of crying – damn this manipulation – came when the four of them get boozed up on limoncello and share confidences. I found this moving. Did I find it believable? Not so much, but I gave in to movie magic.

Then what’s so wrong with a movie like this? What’s so wrong with a world where no one cusses, wounds are always healed, everyone gets together and dances to soundtrack music, and people say things like “No one will ever love you like your nonna did”?

I remember first reading about the man who inspired this story, Jody Scaravella, and his restaurant Enoteca Maria in 2020, on the news site THE CITY. It was during the pandemic, the restaurant was closed, and they were selling jarred sauces made by nonnas of all backgrounds – “Nonnas of the World” the labels read – to keep the business going. The profile focused on a grandma called Rosa Correa who made aji amarillo sauce, “a thick and flavorful Peruvian sauce” …

“It goes with beef, chicken, pasta. I mean, it’s a sauce that you can eat with many things,” Correa, 77, told THE CITY in Spanish. “People should know it, right? I hope they like it – at least Mr. Scaravella did. I’m happy about that.”

New York City was slowly coming out of lockdown, and vaccines weren’t widely available yet. I was working remote, and my good and great husband Damian was an “essential worker,” hauling ass across town at Trader Joe’s. I loved the spirit of the article, the heart and inclusivity, and I was wondering if it was frivolous to bulk-order some aji amarillo, or maybe the “spicy tamarind sauce” they mentioned made by Trinidadian nonna Pauline. Nonna Adelina made suga alla norma, which also sounded nice, but that was something I could cook up myself. I remember thinking I hoped this little restaurant would make it through the pandemic.

And they did. They did just fine. They did better than fine: they thrived, they grew. I looked at their website, Nonnas of the World and see that they’re planning a not-for-profit with a mission to “strengthen intergenerational bonds, combat elder isolation, foster resilience in a changing world, and promote cross-cultural understanding and cultural awareness.” This suggests things much bigger than just a restaurant, and not in a backward-looking, you-feel-it-in-your-heart kind of way. It points to an awareness of a wider world, and concerns well beyond those of a little enclave.

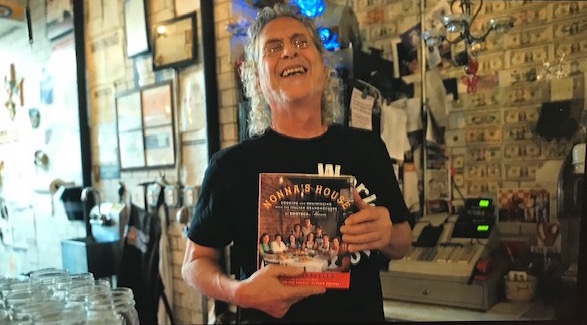

I read that the real Scaravella cried through the screening of Nonnas. That’s sweet, plus the man can do whatever he wants, and God knows he’s earned it. In the last scenes of the movie, when Enoteca Maria has taken off and it’s full to bursting, there are all kinds of non-actor-looking people in the restaurant, a welcome break from the shiny and relentless artificiality of what we’ve been seeing on the screen. One who stands out is a dude with long curly gray hair who looks like he could be a roadie for Megadeath. Turns out that guy is Scaravella! It’s a mug’s game to guess what’s “truth” and what’s “fiction” in a movie like Nonnas, but all this made me think the reality of his experience had to have been much weirder, messier, and more checkered than this cheeseball production suggests.

Nostalgia, however, is not about complexity. The hit has to come simple and sweet and familiar. Never mind that along with this comes a rewriting of history: bad things become not so bad then ultimately rosy. What does it say that the childhood rendered in this movie looks to me so like representations of the fifties, which functions as a shorthand for a time before John Q. Public had to cede power to those pesky Blacks, queers, radicals, equal-rights-seeking women, etc.?

But I’m less picking on this particular movie than wondering why such a thing is so appealing to so many. Is the craving for this storybook Italian American past so strong because it never really existed? How much hurt and pain and exclusion is contained in that craving? Why are people so happy to embrace the most reductive, flattening clichés about Italian Americans? Some good food, some good red wine, C’è la luna mezzo mare on the jukebox, everyone gets up and dances, and everything’s great. Everyone loves you, they really do! It’s a dream of inclusion, an impossible one. And it’s a story that’s told at the exclusion of much deeper stories.

Sadly, I found myself wondering how many people book a table at Enoteca Maria expecting to see nonnas Lorraine, Brenda, Talia, and Susan cooking for them – and are bitterly disappointed not to find them there.

Or maybe the dream is to find your nonna there, in this fantasy tableau, a perfect version of her, uncritical, kind, wholly accepting. Always there to feed you and love you as she remains unchanging, gently smiling, with no needs of her own, and you age but are forever treated like a cherished little child. Is this actually a conjuring of the pagan Ceres or the Virgin Mary? “No one will ever love you like your nonna did.” I think again of my grandma Elsie, who I don’t remember as ever having a word of tenderness for me. There were too many grandkids and she was just too busy cooking. She did once call me a testa tosta – a hothead – for going on about something, when what I really should do is just shut up and eat. Elsie was justifiably famous in my family for knocking out my dad with a shovel when he was a little boy. It was punishment for getting caught in a lie. I’m sure that taught him something, but I’m also sure there had to have been a better way.

Hmm, I wonder whose genes in me made me a hothead?

“No one will ever love you like your nonna did”? Thank GOD.